Memory

A PERSONAL FAREWELL TO MILOVAN VITEZOVIĆ (1943–2022), A WRITER WHO HAPPENED TO THE PEOPLE

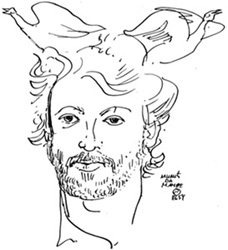

A Ballad of a Knight

He wrote more than forty books, in about two hundred editions, in eleven languages. He is included in more than fifty Serbian and international anthologies. Serbian and Slavic academician, president of the Association of Writers of Serbia. His novels, poems, aphorisms, TV series and movies stand as a high value of Serbian culture. While awarding the ”Vuk Karadžić” TV series with the European Award, Umberto Eco said that it was a sublime fresco of both Serbian history and European Culture. (…) Milovan Vitezović has been with us since the first day and first edition. Our pages and memories are full of his traces

By: Branislav Matić

The sound of a stick on an empty pavement.

The sound of a stick on an empty pavement.

Footsteps of a man leaving, silently, into the distance and silence.

As a great gentleman: ”I left. Everything people had said remained behind me, like a disappearing wisp of fog. And everything they had done, I carried on the palm of one hand.”

*

We heard the news in Kosovo, while attending programs in the ”Vuk Karadžić” City Library in Mitrovica and Institute of Serbian Culture in Leposavić, observing the 130th anniversary of establishing the Serbian Literary Cooperative. Dragan Lakićević is sitting next to me, showing me a message that has just arrived. A newspaper is asking him to send a statement regarding the death of Milovan Vitezović. This is how we found out.

It was a new shock to us, already shocked. Only two days earlier, on March 20, Mrav passed away, Dragan Mraović (1947–2022), poet, interpreter, professor, Vitez’ close friend. A moment of silence at the beginning of all remaining programs seems to last until the very day. And there are certainly many things to be said. ”What you know, what you are witnessing, be sure to write down. From a convenient anecdote to important events, it’s all the same, be sure to write it down”, Milovan used to tell me. ”If we, who were there, who saw, heard, knew, do not do it, it will disappear forever. It will sink into oblivion and forgery. If you write down at least a small note, a small mention, someone will catch it once, lean on it, start from it. It is a seed of history and culture, the building tissue of our novel.”

It was a new shock to us, already shocked. Only two days earlier, on March 20, Mrav passed away, Dragan Mraović (1947–2022), poet, interpreter, professor, Vitez’ close friend. A moment of silence at the beginning of all remaining programs seems to last until the very day. And there are certainly many things to be said. ”What you know, what you are witnessing, be sure to write down. From a convenient anecdote to important events, it’s all the same, be sure to write it down”, Milovan used to tell me. ”If we, who were there, who saw, heard, knew, do not do it, it will disappear forever. It will sink into oblivion and forgery. If you write down at least a small note, a small mention, someone will catch it once, lean on it, start from it. It is a seed of history and culture, the building tissue of our novel.”

I am writing down, my good Milovan. To add to the disappearing wisp of fog.

IN THE PREVIOUS MILLENNIUM

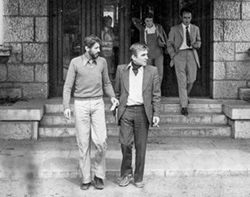

I met him in mid-1980s, soon after my arrival to Belgrade to study at the university. Our roads crossed in the circle of Belgrade aphorists, at satire evenings and kafanas, censers of Belgrade spirit and style at the time. He was near his climax, and I was a beginner. However, he embraced everyone, helped everyone not to miss the road in front of them. You, a kid, still an undigested provincial, enter ”Zora” and hear the laughter of Momo Kapor and reciting of Brana Petrović, Aca Sekulić, Pera Pajić. You enter ”Vidin” and see a symposium at a table in the corner: Kašanin, Mihailo Đurić, Vasko Popa, Milovan Vitezović. If you want to see masters of journalism, you go to ”Grmeč”. (…) If anyone wandered to a place they didn’t belong to, they left quickly. Even spies.

I met him in mid-1980s, soon after my arrival to Belgrade to study at the university. Our roads crossed in the circle of Belgrade aphorists, at satire evenings and kafanas, censers of Belgrade spirit and style at the time. He was near his climax, and I was a beginner. However, he embraced everyone, helped everyone not to miss the road in front of them. You, a kid, still an undigested provincial, enter ”Zora” and hear the laughter of Momo Kapor and reciting of Brana Petrović, Aca Sekulić, Pera Pajić. You enter ”Vidin” and see a symposium at a table in the corner: Kašanin, Mihailo Đurić, Vasko Popa, Milovan Vitezović. If you want to see masters of journalism, you go to ”Grmeč”. (…) If anyone wandered to a place they didn’t belong to, they left quickly. Even spies.

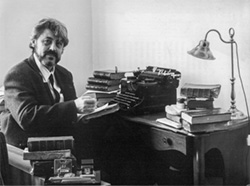

Milovan was a bit over forty years old, twenty-odd more than us, newcomers. Still in full strength, handsome, poetic, quick-witted. Sharp and clever. Behind him were awarded and forbidden books, an entire collection. He waited with a volley, linguistic, everything life and day would throw at him. He loved to score, although he never counted. The game was important to him, not the result. He wrote great things at home, alone, never hiding what he was doing, and scattered aphorisms, epigrams, causeries along his daily roads.

”The important things you have to write will never be taken by anyone else, because they cannot take it”, he used to say. ”You are the only one who can waste it, if you don’t do what is up to you.”

I thought that being a satirist in power or supporting the government was self-cancelation. I claimed that this was taking Serbia into darkness, into turning everything upside-down. I despised projected dissidents and writers who were not ready to suffer for their writing. Milovan left space for consideration and shades. He was old enough; he used his experience. He had the maturity and goodness, so he did not, like we, arrogant kids did, fall into the trap of judging people.

I thought that being a satirist in power or supporting the government was self-cancelation. I claimed that this was taking Serbia into darkness, into turning everything upside-down. I despised projected dissidents and writers who were not ready to suffer for their writing. Milovan left space for consideration and shades. He was old enough; he used his experience. He had the maturity and goodness, so he did not, like we, arrogant kids did, fall into the trap of judging people.

When the war started and times became dead serious, I stopped visiting the Belgrade Aphorist Circle. I believed that satirists should be on hold, and jokers should be silent. Milovan thought the same; that is how he understood the nation and the state, because in his essence he was a man of culture and art, not ideology.

Almost fifteen years later, I am with Milovan again. We are sitting under canopies, in the garden of Captain-Miša’s edifice, across the street from the building he was living in. It is late summer of 2005, gilded and beneficial September. I am making the Evropa nacija (Europe of Nations) magazine and I want Milovan to explain smart readers why Karađorđe means freedom and Miloš means state. Why Europe has a chance only if it is structured as the name of my magazine. Why culture is the measure of  how historical a nation is and how villains are preparing Serbs to be questioned in that matter as well. Why Vuk Karadžić is ”the great joy of Serbian language” and how he alone, like an entire institute, synthetized all previous views of the Serbian language (Orfelin, Dositej, Mušicki, Mrkalj, Milovan, Solarić). Why Serbs lost their epochal political, economic, and military battles first in the area of culture and ideas, without even being aware that they were fighting them. How a traffic accident from 1992 was perhaps a finger of God for Milovan; it made his life more difficult, but saved him from dangerous political traps of that time.

how historical a nation is and how villains are preparing Serbs to be questioned in that matter as well. Why Vuk Karadžić is ”the great joy of Serbian language” and how he alone, like an entire institute, synthetized all previous views of the Serbian language (Orfelin, Dositej, Mušicki, Mrkalj, Milovan, Solarić). Why Serbs lost their epochal political, economic, and military battles first in the area of culture and ideas, without even being aware that they were fighting them. How a traffic accident from 1992 was perhaps a finger of God for Milovan; it made his life more difficult, but saved him from dangerous political traps of that time.

Milovan did it (”Trained Extinction of the State”, Europe of Nations, issue 3, October 2005). He explained. I am signing it with the name Stanislav Božić because of my own rule: one author cannot sign more than one text in a single issue. We are not writing newspapers, we are writing for them. Newspapers in which three or more texts are signed by one man become a private bulletin. Second-grade.

Milovan is nodding his head. He likes the rule.

RECOGNIZING ABUNDANCE

When we started with National Review ”Serbia” in 2007, Milovan was, together with Momo Kapor and academician Dragan Nedeljković, one of the first associates. He was writing from the very first issue: ”I, Karađorđe”, ”Omen of the Holy King”, ”Tears of King Petar”, ”The Pain of a Great Generation”, ”Serbian Socrates and the Call of Freedom”, ”Branko Radičević in Belgrade: Laughing as an Ember”, ”Jovan Dučić having Coffee with Nušić: Drumming Fingers on a Sarcophagus”, ”Ivan Jugović, the Most Trusted Man of Vožd Karađorđe: A Man of Great Mission”, ”Murmur of the Dismissal of Aleksandar Ranković, in

When we started with National Review ”Serbia” in 2007, Milovan was, together with Momo Kapor and academician Dragan Nedeljković, one of the first associates. He was writing from the very first issue: ”I, Karađorđe”, ”Omen of the Holy King”, ”Tears of King Petar”, ”The Pain of a Great Generation”, ”Serbian Socrates and the Call of Freedom”, ”Branko Radičević in Belgrade: Laughing as an Ember”, ”Jovan Dučić having Coffee with Nušić: Drumming Fingers on a Sarcophagus”, ”Ivan Jugović, the Most Trusted Man of Vožd Karađorđe: A Man of Great Mission”, ”Murmur of the Dismissal of Aleksandar Ranković, in  June 1996, in the Life of Returnee Miloš Crnjanski: Emigration Heavy as Rock”…

June 1996, in the Life of Returnee Miloš Crnjanski: Emigration Heavy as Rock”…

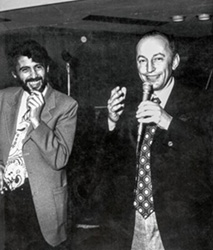

In severe frost, on January 4, 2008, Milovan arrived at the plateau near ”Ruski car”, to the street promotion of National Review. He was handing out free copies with us and talking to readers. He took a photo with a National Review cap, gave statements to TV and radio stations, explained the essence of our endeavor, thickly and deeply. In his own way.

He loved to stop by at our editorial office, to see his people. With Miša’s gentian brandy, we would talk for hours. He was one of the few people able to explain the visionary features of St. Sava in such a way. You rarely meet such a merge of a poet, novel writer, and historiographer. In the same sentence. He knew practically everything about Serbian XIX century, the most important people from the uprising Serbia (who are often not the best-known ones), about rare books from those times. An abundance of information, exciting details, anecdotes, and mishaps. He was master of twists and unexpected bindings. ”As if he were living in that and not his own epoch”, writes a young critic, present twice. ”A power of empathy rarely seen in our contemporaries.”

He did not turn his knowledge into a burden for others. A feature of a master.

He did not turn his knowledge into a burden for others. A feature of a master.

Once, in the antique shop of Peđa Orfelin (1954–2015), we were talking the entire day about the just discovered Menologium from 1719. ”Printed in Vienna, based on a Russian template, on twelve copperplate sheets, with over four hundred miniature Menaion presentations”, that copy placed the appearance of the first Serbian Cyrillic book in the XVIII century as many as twenty-two years before Žefarović’s Stematography. When one listens to Milovan and Peđa Orfelin talking about old books, it sounds as if two Alexandrian Libraries sat at a table and started talking. A few days ago, they met again, in Lešće, the ridge over the Danube and Celtic Belgrade, gazing towards Starčevo and Vinča. Peace be upon them.

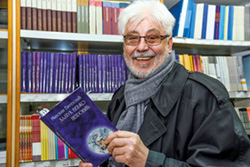

Milovan had a remarkable personal library. First editions of many Serbian milestone-books from the XVIII and XIX century, all old Serbian histories, all pillars of poetry. And he knew them all, in incredible details. I remember how joyful he was when, somewhere from Pannonia, the first edition of Rajić’s history arrived to him.

Milovan had a remarkable personal library. First editions of many Serbian milestone-books from the XVIII and XIX century, all old Serbian histories, all pillars of poetry. And he knew them all, in incredible details. I remember how joyful he was when, somewhere from Pannonia, the first edition of Rajić’s history arrived to him.

I admit that only in those long conversations I truly realized the greatness of that man and the abundance which his literature was flowing from. (Then it is even more difficult to stand the present cheeky charlatans, champions of trivial and colonial literature, who are purchasing Andrić’s, Meša’s or Crnjanski’s awards, just as they will fix Vitezović’s award in the future.)

WITNESS OF AN EPOCH

He loved anecdotes as a way to depict characters, spices of histories. And he always had a handful of them, to fire up the sparkle of conversation. He loved memoirs and personal acquaintances, firsthand histories, what was slipping away from historiography and what only literature can preserve.

He loved anecdotes as a way to depict characters, spices of histories. And he always had a handful of them, to fire up the sparkle of conversation. He loved memoirs and personal acquaintances, firsthand histories, what was slipping away from historiography and what only literature can preserve.

While Milovan was renting an apartment in Resavska, he used to walk with Vasko Popa every morning to his editorial office and then returned to his own. Vasko worked in ”Nolit” in Terazije and Milovan in the Television, in Takovska street. They would meet in front of Vasko’s building in 26, Bulevar revolucije street, across the street from the Church of St. Mark, and walked slowly to the Parliament, then over the Square of Marx and Engels (present Nikola Pašić Square) to ”Bezistan”. They would complete their conversation with a coffee there and continue their own way. ”In the last period of our joint walks to work, Vasko was somehow depressed, something was torturing him, as if he was fearing something. There was a great pressure on him, from the outside or from the inside, I don’t know”, remembered Milovan.

He visited Desanka Maksimović in her apartment above the Serbian Literary Cooperative. ”Inside the apartment she was reserved, sometimes praised the  comrades and system; then, in the hallway in front of her apartment, she would give a sign with her eyes that the apartment is wired and that I should not ask her anything there.” They went to Brankovina together several times, and sometimes Milovan would continue over the mountain to his Kosjerić. Of course, it is no accident that the novel Miss Desanka is part of his opus.

comrades and system; then, in the hallway in front of her apartment, she would give a sign with her eyes that the apartment is wired and that I should not ask her anything there.” They went to Brankovina together several times, and sometimes Milovan would continue over the mountain to his Kosjerić. Of course, it is no accident that the novel Miss Desanka is part of his opus.

He listened to several lectures of Duško Radović in ”Takovski grm”.

In the oversized residential coffin on the corner of Gospodar-Jovanova and Filipa Višnjića streets in Dorćol, Meša Selimović lived on the eighth floor. Milovan vividly told me about the encounters with that delicate and honorable man, great master. He walked with Ivo Andrić from the Palace Park to the belvedere in the Fortress and back. It happened rarely, but he memorized every word. Andrić, by the way, liked to walk alone, immersed in thoughts, on the same route, at the same time. You could set your watch according to him.

The picturesque novel Burlesque in Paris was created from Milovan’s encounters with Miodrag Bulatović. We will not recount, read it yourself. Equally impressive, sometimes robustious, was his companionship with Danilo Kiš. One anecdote clearly testifies how much Danilo trusted him. Milovan tells:

The picturesque novel Burlesque in Paris was created from Milovan’s encounters with Miodrag Bulatović. We will not recount, read it yourself. Equally impressive, sometimes robustious, was his companionship with Danilo Kiš. One anecdote clearly testifies how much Danilo trusted him. Milovan tells:

”In the year 1987, we gathered at the July 7 Award ceremony. Danilo was handed the award and it was, as usual, followed by a cocktail party. Danilo was already severely shaken by his illness and had only returned from his treatment in France. His family took care so that he would not light a cigarette or take a drop of alcohol. In the crowd, Danilo took my hand and took me to the side. Listen, he said, go and get me a tea, but pour a double grappa inside. I looked him into the eyes and said nothing. I did what he said.”

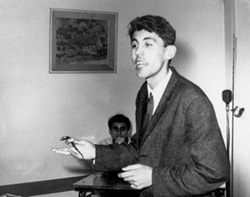

Particularly touching is Milovan’s memory of Crnjanski, the elegiac serenity and Stražilovo sadness. I forced him to describe a crucial episode in the eighth issue of National Review, in August 2008. Now we know that Crnjanski was, from several sides and for a long time, persuaded to return from emigration. He accepted only after receiving personal guarantees from Aleksandar Ranković, vice president of Yugoslavia and chief of Udba secret service. However, only two and a half months after his return, in June 1966, during the recording of the Literary Club with Vitezović in Radio Belgrade, Crnjanski found out that Ranković was dismissed in Brioni, perhaps even arrested. And that even the return of Crnjanski could be assigned as a sin to him. Young Milovan happened to spend the dramatic night with shocked Crnjanski. ”There was a scent of linden trees in Makedonska Street, and we walked this short route for a long time. I was chatty and frivolous along the way. Crnjanski was immersed in thoughts and silent…” Read it.

Particularly touching is Milovan’s memory of Crnjanski, the elegiac serenity and Stražilovo sadness. I forced him to describe a crucial episode in the eighth issue of National Review, in August 2008. Now we know that Crnjanski was, from several sides and for a long time, persuaded to return from emigration. He accepted only after receiving personal guarantees from Aleksandar Ranković, vice president of Yugoslavia and chief of Udba secret service. However, only two and a half months after his return, in June 1966, during the recording of the Literary Club with Vitezović in Radio Belgrade, Crnjanski found out that Ranković was dismissed in Brioni, perhaps even arrested. And that even the return of Crnjanski could be assigned as a sin to him. Young Milovan happened to spend the dramatic night with shocked Crnjanski. ”There was a scent of linden trees in Makedonska Street, and we walked this short route for a long time. I was chatty and frivolous along the way. Crnjanski was immersed in thoughts and silent…” Read it.

GREAT BUILDING IN LANGUAGE

Milovan considered a day without writing as a day that did not dawn. Besides writing, he put three ordinary days into each one of his own. That is how he managed to do everything he had to. In crucial moments of creation, he retreated, became a monk of words, servant of stories. I remember how he described his study at the time he was, in the 1980s, writing the first version of the series about St. Sava. ”Everything was covered with cards with notes, data, small parts of the story: walls, windows, furniture, door. Open books everywhere, with bookmarks sticking out. No one was allowed to enter the room when I was not there, and I walked towards my desk through strictly determined paths…” Sometimes he would hear

Milovan considered a day without writing as a day that did not dawn. Besides writing, he put three ordinary days into each one of his own. That is how he managed to do everything he had to. In crucial moments of creation, he retreated, became a monk of words, servant of stories. I remember how he described his study at the time he was, in the 1980s, writing the first version of the series about St. Sava. ”Everything was covered with cards with notes, data, small parts of the story: walls, windows, furniture, door. Open books everywhere, with bookmarks sticking out. No one was allowed to enter the room when I was not there, and I walked towards my desk through strictly determined paths…” Sometimes he would hear  voices, fragments of conversations, poems told by heart, salutary laughter. Then he knew that he was accepted among the ones he was writing about. He would take his pen and would not leave his home for days, weeks. He would disappear here and dive out there, in Nemanja’s court, in Mt. Atos skits, under Miloš’s porch, in Sava Tekelija’s library. He would board a ship in Szentendre to Zemun. He would follow the measures of Vuk’s stilt on Viennese cobble roads.

voices, fragments of conversations, poems told by heart, salutary laughter. Then he knew that he was accepted among the ones he was writing about. He would take his pen and would not leave his home for days, weeks. He would disappear here and dive out there, in Nemanja’s court, in Mt. Atos skits, under Miloš’s porch, in Sava Tekelija’s library. He would board a ship in Szentendre to Zemun. He would follow the measures of Vuk’s stilt on Viennese cobble roads.

”For God sakes, Milovan, what is with you? You are writing about Vuk, living in Vuk’s street and walking like Vuk?” Slobodan Milošević teased him, in a friendly way, after previously putting a high-rank medal on his lapel.

Milovan laughed while telling me about the episode with then president of Serbia. He was not angry. And we laughed together to a repeating anecdote.

Milovan laughed while telling me about the episode with then president of Serbia. He was not angry. And we laughed together to a repeating anecdote.

At the exit from National Review, the right door leads outside, to the yard and the street, and the left door to the toilet. Since he was born left-handed, right-handed only by training and someone else’s decision, Milovan was always pulled to the left. And always, instead of on the street, he ended up in the toilet. He would quickly correct himself, but the mistake repeated numerous times.

”Milovan, man, stick to the right-wing! The left-wing has always led you to a dead-end!” I joked. ”You know what St. Simeon said: God’s people on the right side, others on the left. Don’t let them trick you, Milovan!”

”Milovan, man, stick to the right-wing! The left-wing has always led you to a dead-end!” I joked. ”You know what St. Simeon said: God’s people on the right side, others on the left. Don’t let them trick you, Milovan!”

He was never angry at me, although he probably sometimes had a reason to be. I joked that it was because I am from Jadar, like Vuk, and because my mother was from the family of Jevta Savić Čotrić. The one with whom Vuk ”began learning books”, the one in whose house in Belgrade Ivan Jugović opened the Great School, forerunner of the Belgrade University. And because, on the male  side, I was from the Herzegovinian wing of the old Vojinović family, from the same roots with famous Miloš, Lujo, Ivo, even Russian writer Vladimir Vojinovich from Slavjanoserbsk.

side, I was from the Herzegovinian wing of the old Vojinović family, from the same roots with famous Miloš, Lujo, Ivo, even Russian writer Vladimir Vojinovich from Slavjanoserbsk.

”You cannot be angry at such people”, smiled Milovan.

When I was preparing Hyperborean Chronicles, he offered to write something about the book. He did it with a pen, in his beautiful handwriting, in small letters, on a carefully cut A5 format piece of paper. He brought it to the editorial office one afternoon, in April 2015, asked me to read it out loud, and then tell him ”if it was any good for me”. I published the entire text in my book, without even moving a single comma. ”Your heart betrayed you again”, I told him.

When the book was published, he asked for two copies. One for him, and the other for the library-legacy he wanted to give as a gift to Kosjerić, his homeland. Both with an inscription.

We wrote ”in four hands” several times. The Great Serbian Visionaries booklet is particularly dear to me. It was printed in 100.000 copies and  distributed with the Politika daily in December 2009. Milovan took over the chapters about the most famous ones, because it is more difficult to write something that no one knew about them. I was writing about Lazar the Serb, Dimitrije Mitrinović, Lazar Komarčić, as well as the chapter about the mystic known by the name of Nikola Tesla. The twenty-eighth booklet from the Meet Serbia edition was piratized on the internet more than any other. (...)

distributed with the Politika daily in December 2009. Milovan took over the chapters about the most famous ones, because it is more difficult to write something that no one knew about them. I was writing about Lazar the Serb, Dimitrije Mitrinović, Lazar Komarčić, as well as the chapter about the mystic known by the name of Nikola Tesla. The twenty-eighth booklet from the Meet Serbia edition was piratized on the internet more than any other. (...)

Milovan, alas, departed. He stopped worrying about earthly issues. Soon, everything marginal and accidental will disappear from our thoughts about him. All the hidden things, calculations, mutual disagreements. We will measure him with the emptiness left in Serbian literature, culture, and the spirit of the capital city after his departure. We will value him by the only thing he should be valued by: his works. A great building in language.

*

The sound of a stick on an empty pavement.

Footsteps of a man leaving, silently, into the distance and silence.

As a great gentleman: ”I left. Everything people had said remained behind me, like a disappearing wisp of fog. And everything they had done, I carried on the palm of one hand.”

***

A Small Inventory List

Milovan Vitezović (Vitezovići near Kosjerić, 1944). Educated in Tubić, Kosjerić, Užice and Belgrade. He graduated at the Faculty of Philology (General Literature Department) and the Faculty of Drama (Dramaturgy Department). He was editor of several newspapers, editor of the Feature Program and editor in chief of the Artistic and Entertainment Program of RTS (1977–1999). He was professor of film and TV scenario at the Academy of Arts since 2001. He wrote more than forty books in almost two hundred editions (thirteen novels, six books of aphorisms, eight books of poems for children, five movie scripts, eleven TV dramas and series scripts, five theatrical texts…). Published books in German, English, Romanian, French, Italian, Slovenian, Macedonian, Russian, Hungarian, Greek. Included in more than fifty Serbian and international anthologies. (…) Member of the Republic of Serbia Academy of Sciences and Arts (since 2021) and International Slavic Academy (since 2020). President of the Associations of Writers of Serbia. Winner of numerous local and foreign literary awards, as well as two medals of the Serbian Orthodox Church (Order of Despot Stefan and Order of St. Sava).

He passed away on March 22 in Belgrade.

***

Books

I have a myriad of Milovan’s books with inscriptions. I also keep an edition of ”King Petar’s Sock” in Russian. He loved to give gifts.

In case of expensive monographs, when he received a small number of copies from the publisher, he sent me copies in pdf. That is how I read ”St. Sava in Russian Imperial Chronicles” or ”Our Daily Vuk”.

”It is important that it does not remain unread”, repeated Milovan.

***

Branko

Milovan’s novel about the life and death of Branko Ćopić was announced a few years ago in the Serbian Literary Cooperative ”Kolo”, but it never appeared. I know that he completed it at least three times but did not consider it ”ready for publishing”. He went through many archives, public and secret, including security and medical files, and built it all into the novel. It had a documentary feature; it had a literary masterhood. Still, something was bothering him. He insinuated something in conversations. I think, however, that the crucial reason was because some people, who did not have a positive role in the death of Branko Ćopić, were still alive, in old age.

***

Member

Several times he raised the question of Miša’s and my membership in the Association of Writers of Serbia. He said that he, as president, had the right of membership ”by invitation”, without boring and a bit farse-like procedure. He knew that, besides the Library and Serbian Literary Cooperative, I have never been a member of anything and that I was sticking to it. He claimed that I have to, that it is a guild, not a lodge or party, and that we have to help him make the Association more serious, to raise its quality. ”When it matures”, he said, ”you just call me. I’ll worry about the rest.”

There was no time for it.